There is widespread agreement across the pharmaceutical industry that the vast majority of trials fail to meet their timeline targets. This article makes the case that a significant part of the answer may lie in the inability of both sponsors and CROs to get to grips with clinical trial risks and uncertainties.

Clinical trials are at the heart of the drug development process. They represent a significant proportion of the total cost and effectively define the critical path to a regulatory submission. Even the most simple study costs over $1m and in the later stages of the development phase they can cost hundreds of millions of dollars and take several years to complete.

In many ways they can be regarded as projects in their own right – they are unique, have their own objectives and have clear start and finish points – and most contract research organisations (CROs) refer to them and treat them as projects. So why is it that there is widespread agreement across the industry that the vast majority of trials fail to meet their timeline targets?

This article makes the case that a significant part of the answer may lie in the inability of both pharmaceutical companies and CROs to get to grips with clinical trial risks and uncertainties. There appears to be an inability to define, understand and incorporate the impact of them and put in place actions to avoid or at least minimise their impact.

Even companies that on the surface appear to have good risk management processes in place often fail to apply them effectively and consistently. Frequently there is just a veneer of risk management in the planning phase for a pharma company or to satisfy the business winning stage for CROs; but it isn’t applied to the conduct of the trial. Added to which the simple spreadsheet risk tools add to the workload but deliver minimal value.

The difference between risks, issues and uncertainties.

Before going too far, it’s important to be clear on definitions. The three terms defined below are frequently used interchangeably which leads to confusion and often results in uncertainty being ignored completely.

Risks are future events that may or may not happen – but if they do they will impact the outcome of the project. They have a probability of happening and an impact if they do. The outcome can be either positive (an opportunity) or negative (a threat). The impact could be on a number of deliverables or attributes of the project which, most obviously, are time, cost and quality – but for a CRO it could also include reputation or the ability to generate repeat business.

Issues are risks that have happened; they are real and have to be dealt with – hopefully, action plans already enacted have reduced the impact and contingency actions have already been drafted and it’s simply a matter of executing them.

Uncertainty on the other hand applies to activities and events that will happen – but there is some variation in the characteristics of that activity, such as its duration or cost, which cannot be fully predicted. A good example of this is the rate of recruitment of patients into a clinical trial – this is not a risk because we know recruitment will happen but it is impossible to be certain of the rate when we are still in the planning phase. All activities have some degree of uncertainty in their durations and costs and the further into the future they are, the more uncertain they are. Providing a single value e.g. a completion date, can be very misleading. It gives a false sense of precision and leads to the belief that if we just worked harder the accuracy of that single value would improve.

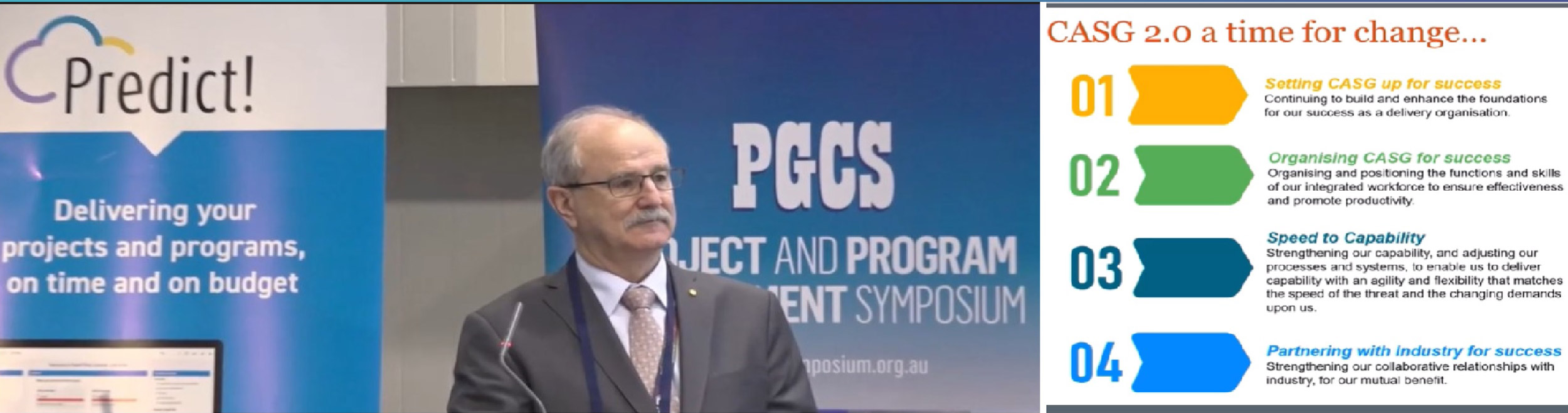

Figure 1. A risk management process should be applied

throughout the clinical trial. New risks and uncertainties may

arise and they need to be managed. A good process, consistently

implemented and supported with modern risk management

tools will greatly improve your ability to hit key targets.

Setting false expectations

In reality, all projects, and clinical trials are no exception, have a mix of risks, issues and uncertainties. Anyone who has undertaken a multi-centre, multi country clinical trial knows just how complex they are. Detailed plans and schedules are developed and we expect these will be ‘right first time’ and will happen exactly as planned. But unless we can predict the future with total accuracy, our experience tells us that in most cases something will not go as planned – protocol sign off is delayed because a senior manager isn’t available, more questions from the FDA than we had anticipated, drug supplies are held up in transit, bad weather stops patients getting to the study centre, the investigators estimates of the numbers of suitable patients is off the mark (and the feasibility study doesn’t appear to have picked this up very well) – but there is a tendency to ignore the possibility that this particular study will suffer from these problems and we promise to hit the targets anyway or we simply say we’ll deal with these if they happen, that the swings and roundabouts will even themselves out and by some miracle we’ll deliver on time… so we stick to the plan and work harder and harder to hit the targets.

The net result is that, euphemistically, ‘optimistic’ timeline targets are set – perhaps already hinting that ‘we’ll be lucky to achieve it’. In reality, totally unrealistic expectations are set; trials are destined to fail before they have even started. It is somehow regarded as a good thing, particularly by senior managers, that we have an ‘aggressive’ plan that they believe will drive performance but what it really does is to demoralise and demotivate staff who will nevertheless strive to achieve the impossible.

Additional challenges for a CRO

The situation can be even more difficult for a CRO. They have the additional burden of needing to submit a bid to secure the work in the first place. Even for very large studies, the bid usually has to be prepared very quickly leaving little time to build a cogent plan. There is a clear pressure to be ‘optimistic’ because that’s what the study sponsors (the pharmaceutical companies) expect – they do for studies they run themselves so why wouldn’t they do it for externally run studies! At this stage, there hasn’t been time to do a proper feasibility analysis using the actual protocol. The CRO either has to rely on recruitment estimates provided by the sponsor – which are probably highly optimistic anyway – or their own numbers for similar studies – which might be not entirely applicable.

Does a feasibility assessment help?

Feasibility assessments to better understand the vagaries of recruitment are commonly used in an effort to ‘de-risk’ the study – although more properly it may or may not reduce the uncertainty! However, the value of this exercise appears to be questioned at every clinical operations conference. Perhaps the flaw in this approach is that investigators who are keen to participate in the study are also likely to be optimistic about the numbers of patients they might be able to enrol – and are they asked to identify local or regional risks and uncertainties? Do they understand even the most basic concepts of risk management?

No one wants to talk about the risks….

An open dialogue between sponsor and contractor is critical to success in all industries and for all projects. All should be working from the same project plan and all parties should understand the risks and uncertainties. Some risks might be better managed by the sponsor and others by the contractor. But for clinical trials many sponsors are not keen to hear about risks and uncertainties – they are regarded as entirely negative. Sponsors want simple single point answers – they don’t want to hear about things that may or may not happen. CROs should simply ‘deal with’ risks and uncertainties because that’s what they are paid for!

So it appears to be the case there is optimism at all levels and a reluctance to recognise and incorporate risk and uncertainty. The end result for the majority of clinical trials is a timeline that has a very low to zero probability of being met. And perhaps one of the most worrying aspects of this situation is that despite the hundreds of trials that are conducted each year – the key lessons don’t appear to be learned and applied to the next round of trials.

What are the consequences?

The consequences of ignoring risks and uncertainties can be seen in a number of ways.

For the pharmaceutical company or study ‘sponsor ‘:

- Acceptance that ‘trials always run late’ has turned the focus on to the starting the trial on time – it’s become a key goal for many companies. Unfortunately, the real value adding step of delivering the results comes with a good deal of forgiveness for late delivery. This culture does not drive improved performance. Of course, if a proof of concept or other key milestone could be achieved and the end of the year is looming – then, as a high priority, additional resources are thrown at the study and the budget ignored in a desperate effort to finish in time to meet the corporate goal.

- Missing key milestone dates – there are many risks and uncertainties associated with drug development, in addition to those specifically related to clinical trials. All of them need to be identified and their impact assessed, and wherever possible actions put in place to reduce/enhance their impact. This is particularly important as a submission date approaches and the financial analysts see promised dates slipping.

- Problematic portfolio resource planning and allocation because of the unrealistic plans. Everyone knows that the milestones are inaccurate, but no one is clear on what they should be and so resources (both $ and people) can’t be used as efficiently as they could be.

- Budget management for clinical trials is challenging. Most trials will have an overall budget for the study, but they are also part of an annual portfolio clinical trial budget. Failing to understand the impact of uncertainty leads to large differences between the forecast spend and the budget. As a result, it’s not uncommon for companies to need to take drastic actions towards the year end – cancelling studies or delaying their starts to the following year, slowing recruitment, etc – to bring the portfolio in on budget. Of course, cancelling studies or moving them to a new financial year directly impacts CROs as well.

- ‘Fixed’ contracts change – the lack of a decent risk analysis and agreed management plan results in numerous issues arising that were not considered or included in the contract.

- Costly and frustrating flood of change orders that result directly from not understanding the risks and uncertainties upfront and the sponsor usually ends up paying.

For a CRO:

- The profit margin is rapidly eroded for a fixed price contract if the trial runs late as the ‘marching army’ costs mount up and other revenue generating projects can’t be progressed. Many such contracts don’t actually turn out to be ‘fixed’ and they end with little prospect for profit. CROs report that for some studies, with hindsight, it would have been better not to have taken it on in the first place.

- Higher risk as performance-based contracts become more common. CRO’s that don’t fully understand the potential for risk and uncertainty to impact performance will be at a strong disadvantage. The danger will be that contracts are taken on that CRO’s have little chance of delivering on time – so any upside is not available to them, or they increase the bid price to compensate for the additional risk – and become uncompetitive.

- The lack of open, mature discussion at the contract negotiation phase means that appropriate risk owners are not assigned – meaning it’s not always clear which organisation should carry the financial burden of addressing the issue or which is best placed to address the risk. A general level of distrust between sponsor and CRO – the expectation is that things will not go to plan and sponsors are quick to blame the CRO.

- The damage to a CROs reputation might be seen as a reduction in repeat business or a move to another supplier.

- The business as a whole is at risk for a CRO that doesn’t understand risk and uncertainty and their impact on profit margin. They rapidly become non-profitable by inadvertently taking on projects with too much risk, at a price that could never generate a profit.

Lessons from other industries

In other industries, such as defence, aerospace or construction, there is a more mature attitude to risk and uncertainty. Rather than trying to ignore it, risk is openly discussed – because both contractor and client know that it’s an integral part of any project. It would be inconceivable for a contractor to bid for work from the Ministry of Defence, for example, without demonstrating that it understood the risks and uncertainties on a particular project and had plans to manage them. Without effective, auditable risk processes in place a defence contractor would be considered totally unsuitable. This open and mature approach to risk means that more realistic plans are developed in terms of both cost and time. By the contractor and client working together, the most appropriate ‘owners’ of particular risks can be assigned – i.e. the part that would progress any mitigation actions and ultimately would be financially accountable for the outcome. Risks are more effectively shared and it’s not all down to the contractor. The fact that this approach is rare in the pharma industry perhaps reflects the relatively rapid change to a greater use of CROs. The relationship in many cases between sponsor and CRO is still adversarial – a situation that parallels the construction industry 20 years ago.

How risk management can help.

Having effective risk management processes and modern tools in place will not guarantee that all clinical trials will hit their timeline targets or budgets. Inevitably some risks will happen even if they are a very low probability. However, it can help in a number of important ways.

- More realistic expectation setting. Risks and uncertainties are identified and their impact on the project plan and schedule is incorporated before targets and expectations are set: enabling actions plans to be defined and funds allocated to mitigate them.

- Quantitative approaches define the probability of achieving particular targets and allow the impact of different strategies to be tested. In this way projects that have little or no chance of meeting a sponsor’s expectations can be avoided – or at least more realistic prices can be negotiated that reflects the increased risk.

- Rapid integration of risks and uncertainties into the bid process: Having a database of key learnings available can allow appropriate risks and uncertainties to be rapidly incorporated into a new project. A risk management tool such as Predict! can greatly enable this process by allowing users to add a number of categories such as country or disease area, etc. CROs with very well developed risk management practices will enable key lessons from previous trials to be rapidly integrated during the bid process.

- Assigning appropriate risk owners at the contract stage allows sponsors and CROs to proactively manage risks significantly reducing the need for change orders.

- Being prepared for risks, both threats and opportunities will help to mitigate or maximise their impact. If an activity completes ahead of schedule are you ready to start the next one and so impact the overall timeline?

- Improved predictability: Risk management greatly improves the predictability of project outcome in terms of cost and time. Consistently meeting key targets greatly enhances the reputation of a project team or CRO.

- Firefighting replaced by proactive management: There is a reduction in the highly inefficient, energy sapping ’fire fighting’ approach to project issues. Effort is applied more productively to moving the project forward.

Conclusions

The lack of adequate risk management processes and tools or their inconsistent application in sponsor companies and CROs is very likely to contribute significantly to the vast majority of trials missing their timeline targets and being delivered late.

The increasing use of CROs has added to the complexity of managing clinical trials. When everything was managed in house, it was clear who would deal with all the problems that cropped up – now there’s another company to deal with. Just how good is the communication and effective management of key risks and uncertainties across this boundary? In most cases project plans aren’t shared never mind risk management plans.

Some may point to the rise in preferred provider or partnering agreements to suggest that this has changed and it’s a much closer relationship now. However, even within those arrangements there still needs to be an open, honest and realistic risk dialogue, effectively implemented processes and modern tools that allow the sharing of risk registers and action plans across organisational boundaries. After all the CRO contribution to the overall success of the project is critical but late delivery impacts the sponsor very significantly.

However, so called partnering agreements will not work for the whole industry – individual CROs cannot support this type of preferential relationship for more than one or two pharma companies. So how will all the companies currently outside these arrangements fare?

At an industry level, risk and uncertainty need to be embraced more openly to enable a more mature dialogue between sponsors and CROs. It’s time to learn the critical lessons from other industries. Without it the pressure on CROs to reduce cost and time with no recognition for the increased risk will put more of them at risk – just as it did in the UK construction industry 20 years ago.

As cost and time pressures continue to grow and sponsors put an even higher premium on performance and may well insist that this is incorporated in the contract, risk management should take a more prominent role in the prosecution of clinical trials and over time we should be able to say with confidence that most of our trials finish on time.